In the past few months the fires in Australia have destroyed the lives of 25 people, over a billion animals, and have decimated over 25.5 million acres of land including over a thousand homes*. As a society we seem wholly unable to solve or even come together to think about climate change, how an unpopular president is elected as leader of the free world, or how the overmedication of Americans has contributed to the opioid crisis despite a generously funded war on drugs. Perhaps the reason we cannot get our arms around each issue is because we fail to think in a certain way. Is it possible then that a thought experiment such as design thinking could change the way we address issues in politics, addiction, and possibly climate change?

It feels brash to suggest we’d cure every societal ill with a simple shift in our thinking, yet many of our essential understandings of the world have emerged from thought experiments. Each thought experiment inspired a new way of solving a persistent problem from the theory of relativity to Schrödinger's cat and my favorite of all time, the Turing Test.

Alan Turing wondered if a computer could fool a human into thinking that the machine was in fact another human. To do so he had to consider what would be required of a machine to appear human to another human. He had to consider the actions that should be programmed into the machine while also anticipating the responses of the real human sitting on the other end of that device. It is because of his ability to think through the questions from the perspective of an ‘other,’ that Turing could prototype and iterate to turn his Turing Test into a Turing Machine.

Thought experiments are the ultimate “what if” because they begin with an urgent question and are followed by a host of wildly varied potential solutions that themselves may produce wildly varied outcomes. If we’re lucky, one of those outcomes may actually work. But we won’t know if we don’t ask.

Turing’s thought experiment birthed artificial intelligence, a concept that if broken into component parts is strikingly similar to the process of design thinking: pose a problem, design a solution, iterate and revise.

Like a good thought experiment, design thinking requires understanding for empathy, or perspective. Solving problems requires distinguishing mere symptoms from the root cause. Addressing symptoms may (for a time) lessen the problem. But only by understanding the perspective of the ‘other’ can you move towards identifying and researching the root cause before designing a solution.

When my son has a sore throat I can give him tea to lessen the pain, but that merely addresses the symptom. If the root cause is a bacterial infection only antibiotics will remove the bacteria and ease the pain. Can we use the thought experiment of design thinking to understand both how we got to this place and how we might actually get out?

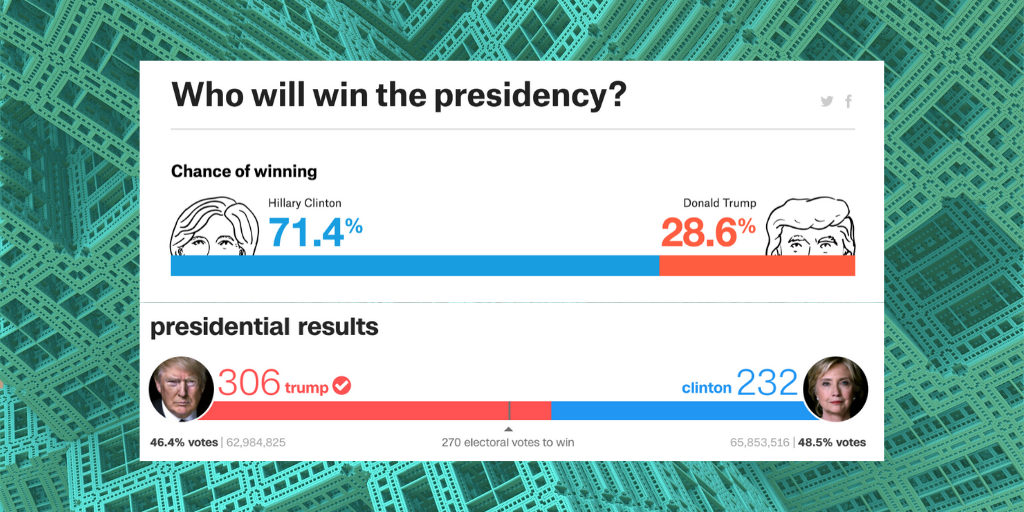

If we were to apply the lens of design thinking to understanding politics, addiction, and climate change we might find that our inherent bias makes it difficult to take the perspective of another or to see the subjectivity of our own beliefs. Let’s explore how an unpopular president was elected despite the poll results.

Understanding for empathy sheds light on the fact that pollsters may not have asked voters the best questions. Perhaps the words used in their questions are themselves subjective or misleading. Or maybe we’d find that people are simply afraid to admit their own latent biases publicly while voting is (at least for now) confidential. If pollsters could anonymously collect information with no way to identify the person on the other end of the telephone line, would we have been less surprised in 2016?

Design thinking is not only a way to approach problem solving, it’s also a way to approach learning. Systematically taking the perspective of others and asking questions forces us to see problems as they exist in the world around us from multiple often times novel positions. Moreover, our questioning, iteration, and revision offers a greater potential for sussing out root causes from symptoms and ultimately making powerful changes in the world around us.

I don’t mean to suggest we currently have answers to all the pressing questions, frankly I don’t believe we are even asking the right questions. But we can get there by inviting new voices into the asking and the solving. For instance, why aren’t we asking children to tell us what they see as the purpose of school and the utility of their learning?

We continue to solve for symptoms (e.g., new sanctions, curriculum, or methods for testing our children) and not for the root cause (e.g., who is served by these sanctions, curriculum, or tests). If we can learn to ask better questions we will have a better chance at identifying and ultimately solving for root causes instead of simply putting band aids on symptoms.

The rain was nice for Australia, but the fires will continue to burn if we do not address the root cause and work to build solutions for a more sustainable future alongside those who will be left to inherit the earth once we’re gone.

*https://www.bustle.com/p/9-australia-fire-statistics-that-show-the-degree-of-its-impact-19777140

Learn more about how design thinking can change the way we think, act, and change the world:

Excerpt of Designed to Learn featured in the Washington Post: http://bit.ly/PrtnyWPArt

Link to Designed to Learn from ASCD: http://bit.ly/PrtnyASCDBk

Link to the Study Guide to ASCD book Designed To Learn: http://bit.ly/PrtnySG

Interview about Designed to Learn on BAM Radio: http://bit.ly/PrtnyInt